Pioneer of the L.A. look: Paul R. Williams wasn't just 'architect to the stars,' he shaped the city https://t.co/p4aSEo4Nvt pic.twitter.com/9X2H8ltciP

— Kevin Clark (@Homageusa) January 16, 2021

Column: Kevin McCarthy lauds the first Black member of the House. Here’s why that’s annoying https://t.co/TWtH2goGiT pic.twitter.com/D6mfcXYkBq

— Kevin Clark (@Homageusa) December 11, 2020

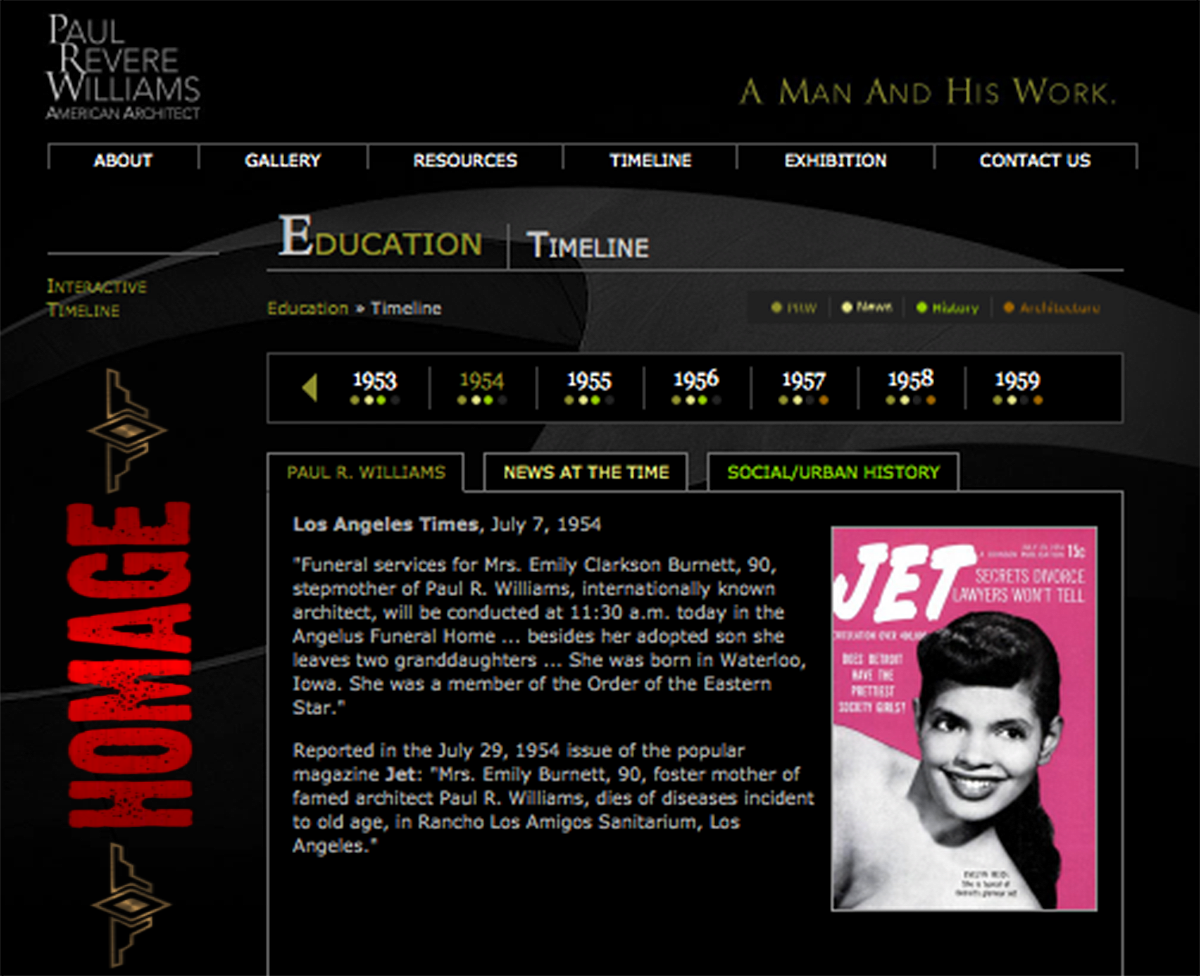

The Digital Pathway Initiative is proud to announce that we’re continuing the interactive timeline of a trail blazer and a man we call “lost black architect” Paul Revere Williams. This timeline will integrate the best in breed immersive and open source tools to provide challenged based learnings for generations-to-come. We’ve found over 3k friends , and a robust instagram of his archived work who have founds this man’s work inspiring and we hope to grow that number through this project.

See inside the lost archive of celebrated Black architect Paul Williams https://t.co/EyfkPzkEn9

— Kevin Clark (@Homageusa) December 10, 2020

Paul Revere Williams was awarded The AIA’s Gold Medal, and the only African American to do so. The award recognizes an individuals work that has a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture. Paul Revere had a client list that reads like a who’s who of Hollywood history, Paul Revere Williams developed an incredible portfolio of nearly 3,000 beautiful buildings during his five-decade career that was marked with a number of broken barriers.

An architect whose work carried the glamour of classic Southern California style to the rest of the world, Williams was the among the first black students admitted to the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, the first black architect to become a member of the AIA, and, later, the first black member to be inducted into the Institute’s College of Fellows.

“Without having the wish to ‘show them,’ I developed a fierce desire to ‘show myself,’” Williams wrote in his 1937 essay for American Magazine, I Am a Negro. “I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, AS AN INDIVIDUAL, deserved a place in the world.” And Dakar wants to make sure that we promote Paul Revere Williams as an inspirational icon to influence the next generation such as’ Tyler Gordon.

Designed by architect Paul Revere Williams in the 1930s, Max Azria’s mansion has 17 bedrooms: http://t.co/jzYTemyeEz pic.twitter.com/it4kveaNIU

— Forbes (@Forbes) May 25, 2015

The profession desperately needs more architects like Paul Williams,” wrote William J. Bates, FAIA, in his support of William’s nomination for the AIA Gold Medal. “His pioneering career has encouraged others to cross a chasm of historic biases. I can’t think of another architect whose work embodies the spirit of the Gold Medal better. His recognition demonstrates a significant shift in the equity for the profession and the institute.”

14-year-old Bay Area painter Tyler Gordon just made the cover of Time Magazine. Literally. https://t.co/DAq2Gf5OnH) pic.twitter.com/WUFPjllpUa

— Kevin Clark (@Homageusa) December 11, 2020

Born in Los Angeles in 1894, Williams was orphaned by the age of four and was later raised by a foster mother who valued his education and encouraged his artistic development. Despite a high school teacher’s attempts to dissuade him from pursuing architecture for fear that he wouldn’t be able to pull clients from the predominantly white community while the black community would not sustain his practice, Williams persevered.

Confident in his abilities, Williams garnered accolades in architectural competitions early in his career while developing tactics like rendering his drawings upside down so that his white clients could view his work from across the table rather than by sitting next to him.

The Beverly Hills Hotel designed by African American architect Paul Revere Williams. pic.twitter.com/iPr8OB6dUl

— Kimberly (@TheKimbino) July 22, 2020

“His obstacles were great, but nothing could extinguish his brilliance. Unable to participate in the ‘old boys’ network that boosted the careers of most architects of the day, he found ways to distinguish himself and garner clients,” wrote Karen Hudson in her book Paul R. Williams Classic Hollywood Style.

Williams opened his practice in the early 1920s when Southern California’s real estate market was booming. His early practice focused both on small, affordable houses for new homeowners and revival-style homes for his more affluent clients. As his reputation swelled, so, too, did his client list. Williams’ practice expanded and among the 2,000 homes he designed include graceful private residences for legendary figures in business and entertainment such as Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Lon Chaney, Frank Sinatra, and Barron Hilton.

A post shared by Really nice spaces and places (@__dreamspaces)

While Williams was more than comfortable with the historical styles endemic to Southern California, his fluency in modernism is reflected in the work outside of his residential practice. Among his number of schools, public buildings, and churches are American architectural landmarks, including the Palm Springs Tennis Center (1946) designed with A. Quincy Jones; the space age LAX Theme Building (1961) designed with William Pereira, Charles Luckman, and Welton Becket; and his 1949 renovation of the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel. Eight of Williams’ works have been named to the National Register of Historic Places.

Regardless of his struggles as a young architect, Williams is a figure whose accomplishments vaulted him into the vanguard of the profession. He stands as one of America’s foremost architects who was able to nimbly adapt to shifts in architectural fashion until his retirement in 1973.